The rigging of the great sailing ship clattered where it caught the howling wind and driving rain. Within the dense, ancient walls of the Moth & Moon inn, two sailors took shelter.

“Come away from the window, boy. The ship won’t come no closer for you pining after it like a puppy.” The old sailor kicked a chair with his boot as he spoke. It screeched on the pitted wooden floor. “I’ve never known rain like it. It hasn’t stopped all day.”

The young sailor sighed and took the chair. “I wish we’d docked at Port Knot instead of here. At least there’d be more to do.”

The innkeeper, Mr George Reed, poured them each another tankard of ale. “I’m sorry we’re not providing enough entertainment for you, lad.”

“Oh, no, I didn’t mean it like that,” the young sailor said. “It’s just…well, there’s not a lot of life about the place tonight.”

He wasn’t wrong. There weren’t many local villagers in. Under one of the many staircases, a duo of young lovers made amorous overtures to one another. By the huge fireplace, a fisherman dozed while his dogs snoozed by the fireplace.

“Why did your crew leave without you?” George asked.

The young sailor avoided his gaze. The old sailor cleared his throat. “We, ah, we were enjoying some…local hospitality upstairs. We didn’t know the others were leaving.” The inclement weather had forced them both to remain ashore, fearful of being stolen by the rapacious waves should they attempt to return to their vessel.

George laughed and put his hand on his hip. “And so you’re stuck here for a while. Tell me, have either of you ever been to Port Knot?”

The sailors shook their heads. The older of the two had sleepy eyes and a plump, weather-belted face. The younger used long, bony fingers to fiddle with his own straggly hair.

George pulled up a chair and sat with his back to the fire. He rubbed his short, grey beard as if trying to remember something. “I had a coach driver from Port Knot in here once. She stayed for three days and three nights. She had this rabbit with her. Big, fluffy thing. I never saw it eat anything, the whole time they were here. It just sat on this table, right there, staring into the fireplace.

“I asked the driver where she found it. She took a big gulp of her ale and leaned back in her seat. She said it had been on a dark and cold evening one October. She’d been working all day and wanted nothing more than to get home to a warm bed. Most of her trade came from the docks but it had been a slow night. As she lifted the reins to set off, the sea turned still as glass and a fog rolled in, quick as you like.

“Out of the mist came this boat, a little rowboat, not making a single sound. No oars in the water. Quiet as the grave. Standing in the boat, a man, thin as a rake, wearing a long coat as green as the holly on the highest part of the bush. His hair, whiter than freshly fallen snow, almost glowing in the moonlight. The driver, she thought it must be a trick of the light, a lantern on the boat illuminating the fog around the stranger.”

The old sailor crossed his arms. “Must have been.”

“Only she didn’t see any lanterns in the boat,” George said. “The little rowboat pulled up against the pier and the stranger in green stepped out. He didn’t bother to moor the boat. He just stepped out and walked right up the driver’s coach, opened the door, and climbed in. The driver, well, she didn’t know what to make of it. She gripped the reins so tightly her knuckles were fit to burst through her skin. She just about worked up the courage to ask where the man wanted to go.

“The stranger’s voice, soothing and lyrical, put the driver in mind of a half-remembered lullaby. “Take me to the darkest place.”

“What do you mean, the darkest place?” the driver asked. “Where’s that?”

“You know where it is. The place where no one goes. The place where no bird sings. Where no child plays. The place with no hope.”

“The driver flicked her reins and the horse trotted on, hooves striking the quiet cobbled streets. She followed the twists and turns of the town, going under bridge and over hump. She went around and around because there isn’t a straight road in the whole of Port Knot.”

“I’ve heard that,” said the young sailor. “You can’t get from one point to the next without crossing your path twice.”

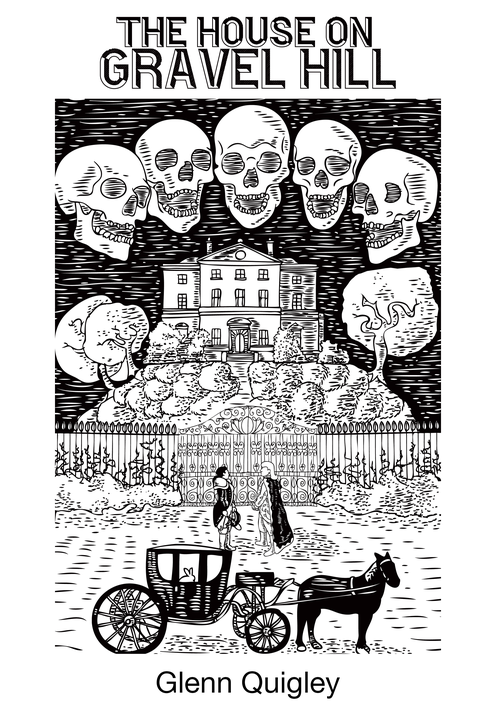

“Finally,” George said, “the driver pulled up outside a rusting, wrought iron gate of a cold and woebegone mansion. Weeds had grown around the railings as if trying to choke the life from it.

“The stranger stepped out of the carriage and for the first time, the driver got a good look at him. At his slender, beautiful face. At his lips red as berries. At his hair hanging long and straight. At his coat embroidered with leaves and shoots that grew from the hem, climbed up his back, and crept down his sleeves. The stranger wore not only a coat but a riding cloak. A riding cloak trimmed with ash-coloured fur. It looked like the fur of the pet rabbit the driver had as a girl. The one with a white diamond on its head, the one her father had taken to the kitchen that winter when they had no food.

“The river Lowena runs mostly underneath the town,” the driver said. “But there’s the secret river too. One even lower. The Anfeus. It runs perpendicular to the Lowena, did you know that? It crosses underneath it at one point, and one point only. Right here. At this house on Gravel Hill.”

“Her horse pulled at the reins and stamped on the road, anxious to get away.

“The stranger pointed to the iron gate. “Open this.”

“The driver wondered why he couldn’t just open it himself but, not wanting to be rude, she wrestled with the latch and swung the gate open. The stranger slipped past, carefully avoiding the metal. He walked along the overgrown flagstones, past the threadbare hedges, past the dolorous willow tree, up to the front door.

“The driver tied her horse to the fence before dashing after him, begging him to stop. “You can’t go in there. No one goes in there.”

“Gravel Hill is one of the wealthiest parts of the town and all around them stood manors and mansions of the grandest sort. This house, though, this house stood out from the rest like a dead tooth, like a broken toe, like a black flag.

“With his elegant hand, the stranger twisted the doorknob and let himself in. The driver hesitated at first but curiosity soon got the better of her, and so she entered the grand house. The damp walls, the missing floorboards, the constant drip, drip, drip of unseen leaks made her flesh crawl. To step into that house on Gravel Hill, one of the oldest in all of Port Knot, was to step into a rotting tree. The house reeked like a marsh; the air so thick as to catch in the throat.”

The young sailor pawed at his own neck before taking a sip of ale.

George grinned, only for a second, then furrowed his brow. “The driver picked her way carefully up the wide, ruptured staircase. Each room they passed more fetid and ruinous than the last. Sodden paper curled away from the walls like the leaves of unloved plants. Candlesticks stood rusted and flaked like bad skin. They turned one corner, then another.

“They went on and on, so far the driver became certain they’d made a wrong turn and had doubled back on themselves, yet each dingy room held furnishings novel to her, each glum and grubby painting different to those she’d seen before.

“At last, they arrived at a small, scarlet hallway that dipped towards an arched door. The hallway became the mouth of a great beast. The closer the driver moved to the arched door, the greater her certainty of being swallowed whole. Sweat gathered on her brow. The stranger in green took the handle and turned it.

“The five figures around the table were dead, you can be sure of that. The desiccated flesh, the empty eye sockets, the maggot-ravished limbs, it all pointed to that one inescapable truth. But it didn’t stop them from talking. “Jack Thistle, you should never have come. Jack Thistle, son of Green Man. Jack Thistle, son of Gwaf. Your tricks and cunning are not wanted here. Return to the hills, return to the dales, sleep again, Jack Thistle, for this is a place of shadow and you have brought light.” Though the voice emerged from the bodies their lips did not move, for in truth they no longer possessed any. Nor did their jaws open and close, for if they did they would have surely snapped off. Rather, the sounds echoed from somewhere much farther away than the throat. “Leave this place, Jack Thistle.”

The old sailor slapped the table with the palm of his hand. “It was Jack O’Thistles himself! Well, blow me down.”

“None other,” George said. “Jack of the Thistles, born between seasons. Jack the Wanderer, raised in hedgerows. Jack the Trick, taught by piskies and drawn to Port Knot by that house on Gravel Hill.

“I think it is you who should leave,” said the pale and beautiful Jack Thistle, his voice like wind in the trees, like a brook in springtime. “You’ve stayed far longer than you should and you’ve brought this house to ruin. Your rot will spread.”

“The voices of the deceased grew louder. “Let it. In life, this town ruined us. In death, let us return the favour.”

“The driver noticed then a ring on the bony remains of a finger. Heavy and golden, with a distinctive engraving the shape of a crowned lobster. “You’re the Exeter brothers,” she said. “You were moneylenders. You squeezed the poor for every ha’penny and every shilling. You left hundreds destitute.”

“All five corpses shuddered with laughter. “We gave them more than they deserved.”

“The driver rubbed her hand lightly across a soggy wall. “The stones of this place were meant for a hospital,” she said. “You diverted them here, used them to build this house instead. How many people died because there was no place to treat them properly?”

“The figure with the ring laughed again. “A ship does not mourn the loss of a rat.”

“Each of the corpses sat before plate, cutlery and tankard. Jack Thistle paced around the table, without an ounce of fear. He lifted a grimy fork, examining it in the moonlight. He held it close to his nose. “Poison.”

“Perfidy!” one corpse said. “The victims of a cruel abuse of trust! We, who sought only to raise the unworthy from squalor, were struck down by a vicious and callous assassin!”

“But who could have done so?” the driver asked.

“The cook!” said one.

“The maid!” said another.

“Or perhaps,” Jack Thistle said, “one of you? One of you who had enough of the lies, and the treachery, and sought to end all of your lives.”

“Slander!” said one.

“Sedition!” said another.

“The bodies rattled with rage as each began to accuse another of heinous deeds committed while still living.

“You, Fenton, were always jealous of my way with women!”

“You, Anton, despised my violin playing!”

“You, Aaron, cheated me of my inheritance!”

“You, Eldon, stole from my bedchamber!”

“You, Barron, scuppered my chances of marriage!”

“The bodies shook with such fury as to cause arms to fall from sockets, necks to crumble, and skulls to roll to the floor. The driver jumped back as a thigh bone crashed to her feet.

“And then, naught but silence. Stillness. The air in the house began to clear. A scent of roses wafted through the room.

“The driver followed Jack Thistle back through the hallways, returning to the front door far more quickly than expected. The house, so twisted by the baleful spirits, had settled back into its proper shape, a shape that once again made sense. They left the mansion and returned to the iron gate. The driver swung it closed behind them, then spoke to her waiting horse, more to calm her own nerves than anything else. Jack Thistle climbed into the coach.

“Which one of them did it?” the driver asked. “Which one of the brothers poisoned them all?”

“Jack Thistle smiled and shrugged. “I don’t know that any of them did.”

“Upon returning to the docks, they found Jack Thistle’s unmoored boat waiting for him at the water’s edge. The driver thought about asking for payment but decided against it. She didn’t want to prolong their time together.

“As Jack Thistle stepped into his boat the driver noticed he had forgotten his riding cloak. She hopped down, opened the door to the carriage, and there on the seat, with a white diamond on its head, and nose twitching, sat the ash-grey rabbit from her childhood. She lifted the animal, stroked its fur, and found it just as soft and warm as she’d remembered. She turned to thank Jack Thistle but found herself alone on the foggy dockside. Just the coach driver and her rabbit.”

George stood, lifted the pitcher of ale, and returned to the bar. Rain lashed the little windows of the inn and the fire crackled in its hearth. The two sailors sat in silence until the older of them cleared his throat. “Wait a moment, Port Knot is on Blackrabbit. The island is crawling with rabbits, one probably just climbed into the coach while they were in the house.”

The young sailor sat upright. “And a tired coach driver, working late, she probably wasn’t thinking straight. I’d wager her eyes were playing tricks on her.”

George took a cloth and mopped up a spillage. “You may well be right. After all, it’s not as if you can go to Port Knot, hail a coach at the docks, and be taken to the house on Gravel Hill by that very driver, now is it?”

“Exactly,” said the young sailor, folding his arms. “Wait. Can you?”

George slung the cloth over his shoulder and leaned on the bar. “Next time you need to seek shelter from a storm, maybe you’ll find out.”

THE END

© 2021 Glenn Quigley. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or modified in any form, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

If you enjoyed this story, consider leaving a tip on my Ko-fi account.

As a thank-you, you’ll get a link to the story in ebook format (PDF, EPUB, or MOBI).

Other books by Glenn Quigley: